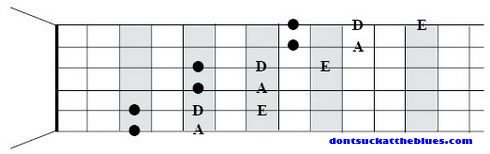

The snake scales answer all of those questions asked in Part One. First, all the positions contain all the same notes so you can change positions any time you want. May I recommend changing on a downbeat to start.

You might want to begin by using the positions that start on the root of the chord that is being played, using the snake scale to get there and back. For example: position 1 for the I chord, position 3 for the IV, 4 for the V. How do you get there? Slide up the snake. On the strings where the snake scale uses 3 notes, slide up from the middle note with your 3rd finger, moving your whole hand into the next position. The middle note is also a note you can bend and you bend it up until it sounds like the note 2 frets higher.

Learn where the Root notes are for all the chords hit them on the downbeats

The snake scale helps you learn where the Root notes are in the scale positions for all the chords in the song. It really helps if you sort of center your riffs around the Root notes of the chords as they change. It sounds more like you are moving with the song that way.

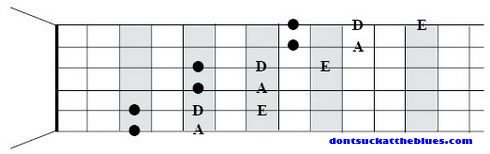

Here’s a cool trick. Notice that the snake scale is set up in octaves. So you can do a riff on the low strings and repeat it over and over in the middle and then up top.

Snake scales are great for repeating riffs in 3 octaves

You need to understand the relationship of Key to Scale to Chord.

Imagine this: there is a band on stage playing a 12-bar blues in the key of A. You are standing there, center stage, in a full house under the big white spotlight in your tight leather pants. On the floor in front of you is your vintage jet black Les Paul with the spotlight glinting off the gold hardware. It is tuned so that it can only play 5 notes in the key of A. The blues scale. In your hand is a bag of rocks.

The colored lights come up and the band is catchin’ a funky groove and you start throwing the rocks at your guitar. The crowd screams with every riff. You skip em, you bounce em, you throw a handful at a time and build the crowd up and take them down. You end by taking a pair of wire cutters and TWANG each string, cutting it in half right at the harmonic. The reviews trickle in, “he never missed a note” one says. “Flawless” says another. Telegrams arrive backstage. Gibson wants to name a guitar after you and the line of groupies goes half around the block.

Wait what?

Silly but it is true. If you are in the Key of A and the scale you are playing is in the Key of A you could throw rocks at it and make music. The whole idea of “The Key” is everyone plays the same notes. All the chords in a Key are built from the notes of its scale. So therefore, if the bass player, the piano player and you throw your rocks at the same set of notes in time with that girl’s boyfriend banging the drummer’s head on the stage you will all sound good together.

It has to be easy. How do you think a stage full of heroin addicts drunk on Jack make such great music? The reason is simple: you don’t need to think. It is better if you don’t. It is better if you throw your fingers randomly but rhythmically at the notes and only the notes of the pertinent scale.

This means that you don’t have to use the string or note next door to the one you are playing. Try bigger intervals, skipping strings and frets. Jump around, go back and forth, up and down, and when you feel trapped in one position use the snake to move to another. Mix in longer runs using the snake scales. It not only sounds good, it looks cool.

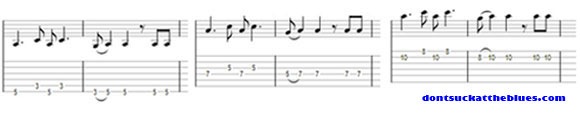

Here is an easy riff that runs up the scale then you can play it backwards. Try and figure out this same riff using the Major snake scale. I’ll show it to you next time, but spot the up and back pattern of this one and I bet you can figure it out. These riffs will help you learn the scales inside and out and you can use them over and over with variations as part of your solos. With some practice they will be solos that don’t suck. Stay tuned, next time we’ll talk about blue notes, hammers, pulls and wiggles.